Mohamed Bellaaziz (37) has a heart for books and poetry, especially Arabic writers. When he is planting tomatoes in his garden and works with the soil with his hands, he feels at ease. He teaches social orientation and integration at Atlas, an organization where immigrants learn Dutch and find their place in Antwerp. “I feel the happiest when I am on the train, in between work and home.”

“Fantasy, daredevil and swimmer are three words I would use to define myself. I feel a certain amount of safety when I am swimming. I enjoy reading and writing poems. I read a lot of literature or novels written by Arabic writers in Dutch. I love when fantasy crosses reality in books.”

“My favorite word in Dutch is ‘fantastisch’ (fantastic). But ‘grauw’ (gray), a word I learned in the Netherlands, is the funniest one. However, it is a bad word in Arabic, thus you would rather not use it. It means “You have shitted”, this makes me laugh every time I hear it.

Mastering in literature

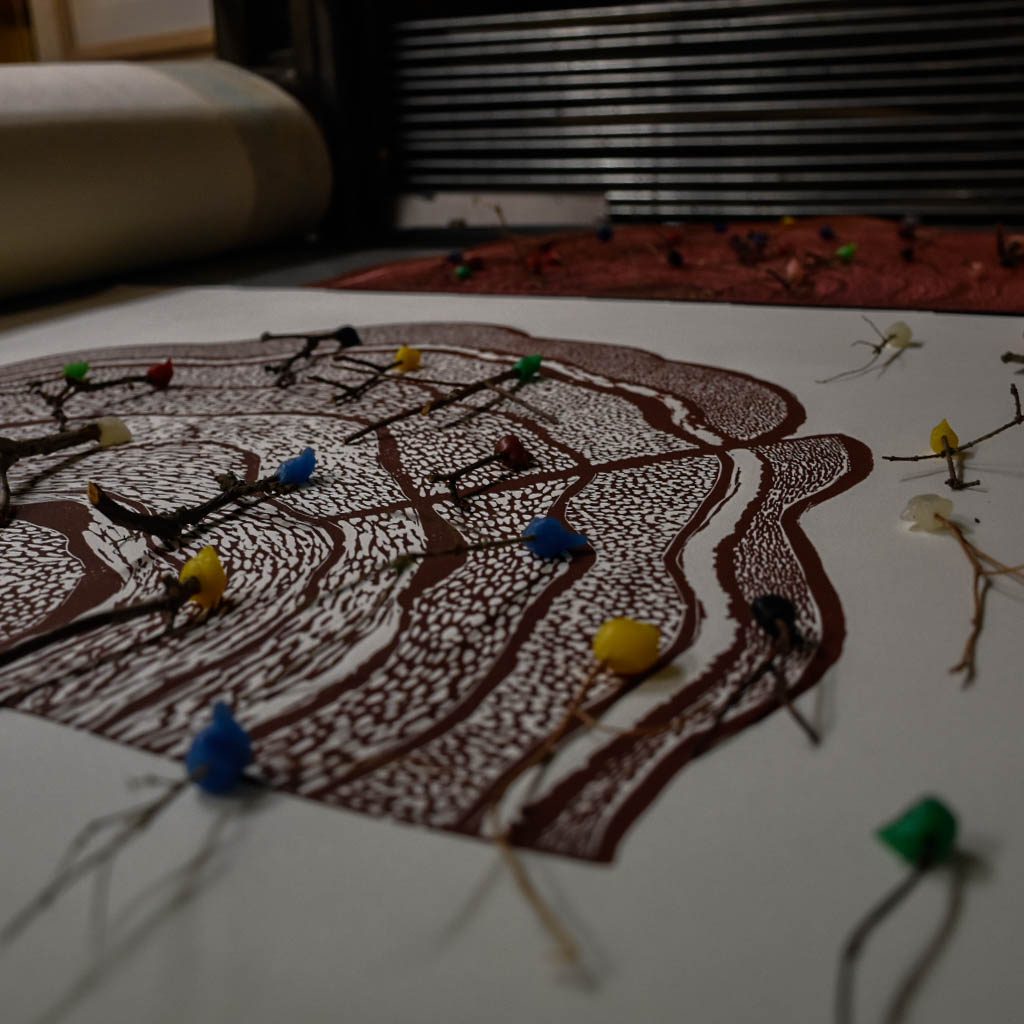

“When I’m in my garden’s greenhouse, I feel most at home. I’ve recently planted my tomatoes and felt really joyful. I am working on the soil with my hands, then I start thinking poetically about it, how we will eventually bury ourselves when we die.”

“I come from Morocco, where we did learn French, but learning Dutch is really difficult. Even though I took the Dutch courses at Atlas when I arrived here I still struggle with the language every day. Atlas motivated me to learn Dutch, I couldn’t be more grateful to be working there right now. When I’m on the train, where I feel at peace between work and home, I read ‘Wablief,’ the newspaper made for non-native speakers.”

“Most Moroccan adolescents dream of immigrating to Europe. I was a teacher and I was happy with my job and my life. But due to my love for books I wanted to get a master’s degree in literature. Furthering education in Morocco is not easy: You have to be good-looking, be from the right region, and have a reputable family. Because of those reasons, I started thinking of moving to another country.”

I am ‘me’, not ‘us’

“in Antwerp, the library was a place where I immediately felt at home. I couldn’t read a word in Dutch in the beginning. Now there are a few books in Arabic, but there were not any when I arrived.”

“The image of Moroccans in Antwerp is not nice, or decent. A Moroccan is often seen a profiteer, as lazy, as someone who sits in a cafe all day. Those cliches are so painful. Sometimes you want to shout ‘I am different, I read poetry and I like working!’ I am frequently asked: ‘Do you work?’ This question may seem normal, but it hurts my soul.”

“I refuse to play the role of a vulnerable person, it has nothing to do with the story of migration. It is connected to humanity. This is a discussion that is ongoing in this country, but it hurts immigrants. You always have to act as a victim. ‘Go live in the diverse Antwerp district Borgerhout. We’ll give you a living wage.’ That’s why I left for a little village in West Flanders where there are not that many Moroccans because I want to be ‘me’ and not ‘us’. I am not the victim here.”

“Some people don’t see me as an individual, but as a part of a group. When I start talking and expressing my opinion, they say: ‘Yes, you think that way because of your religion and culture.’ But that, however, is just my opinion. Yes, my religion influences me, but so do the books and poetry I’ve read.”

By Nina Van Staeyen & Anna Nikolishvili